BUILDING A BETTER MONUMENT

CURATED BY SEPH RODNEY

To Make a Path

How might one respond to several cataclysms happening at once? For many of us precariously making our way relying on strained emotional, fiscal, and institutional resources the current situation can feel overwhelming. Right now in the United States we are confronted with the failure of the state to protect (and thereby equally and appropriately value) marginalized peoples from violence arbitrarily meted out by the state’s own law officers, the incompetent and capricious use of state power to protect and support a white supremacist oligarchy, a collective loss of faith in institutions, and, ultimately, the life-threatening catastrophe of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the face of all this, my answer is: “I don’t know.” But I trust artists.

I trust artists to render these problems in greater clarity, to tease out the ramifications of the current calamities, and to articulate a vision of a place beyond these debacles. Artists do not frequently provide outright answers, but they can and do orient us to the proper questions to ask in a moment that might feel like most responses are ineffective. Artists can tell us that there is something beyond catastrophe and that it is actually possible to live through these times buoyed by the image of what we might bring into being tomorrow.

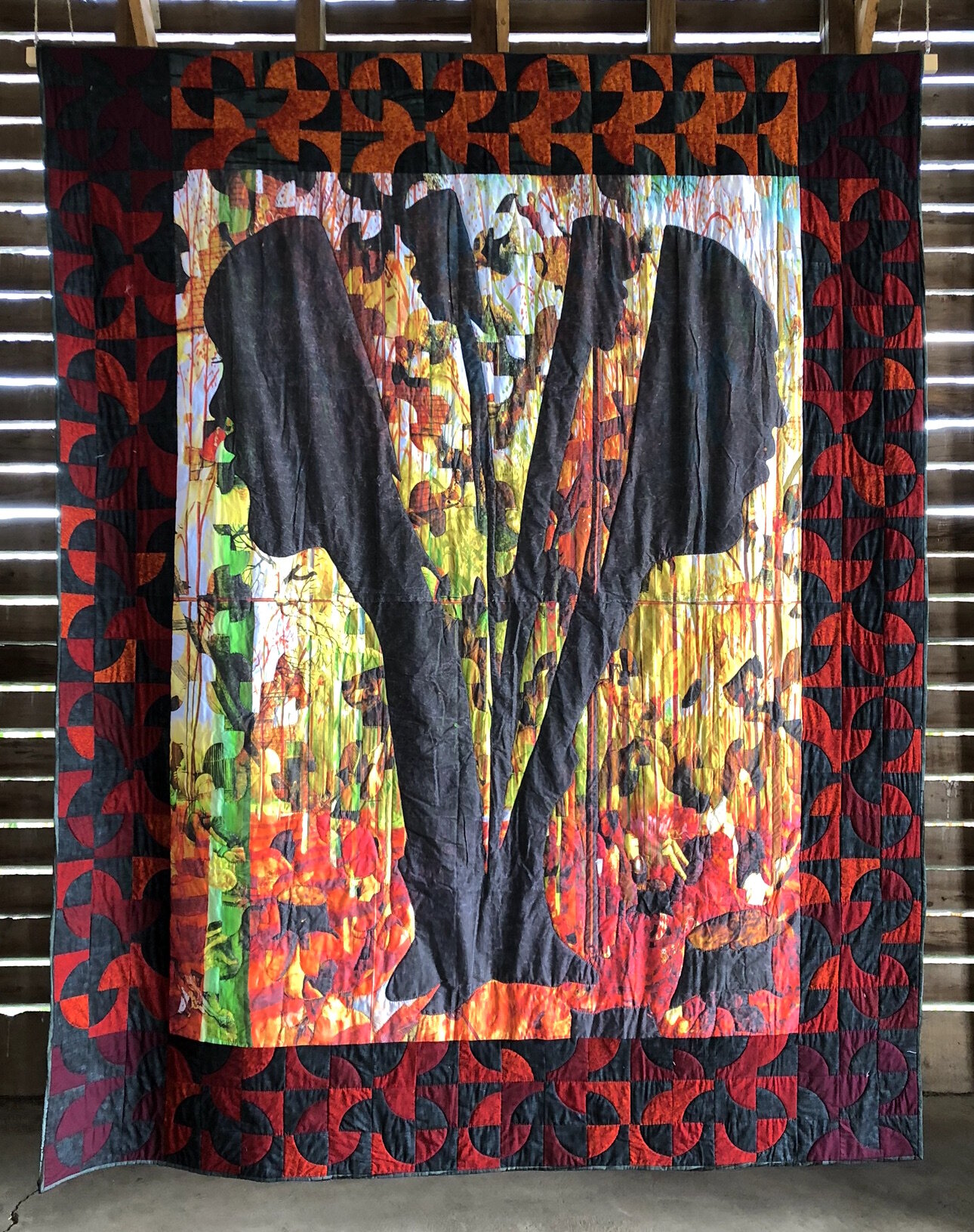

These nine artists do precisely this. This is why they are here, having decided to answer the ringing bell, the full-scale alarm, to put their shoulders to the wheel and help remake our sense of what we should commemorate, what we should revere. Too long this nation has esteemed historical figures that have in no way earned our veneration. So, these artists — Yelaine Rodriguez, Didier William, Yvette Molina, Tsedaye Makonnen, Jesse Krimes, Dominique Duroseau, Alexandria Smith, Kenseth Armstead, and Jori Minaya — all assert a break with that bankrupt tradition, and present to us templates that will invigorate our futures.

Certain of these artists, like Kenseth Armstead, having been working on the issue of monuments for several years and here his work contextualizes George Washington in relation to the Africa subject he sought to deny. Others, such as Yelaine Rodriguez have not explicitly named the monument or public memorialization as their cause, but nevertheless show the Afro-Caribbean subject in full ceremonial regalia, visually proclaiming a woman who has the power and resilience that our myths inherited from US popular culture never could provide. Joiri Minaya gives us a picture of what it would look like if these Afro-Latina women replaced the brazenly colonialist statues of conquistadors with their own bodies of color and vivacity. Tsedaye Makonnen and Dominique Duroseau offer contrasting images of women derived from the African diaspora — regal and austere and conversely shackled and abject. Alexandria Smith pushes the Black woman to the center of myth making, depicting her as the central character of her own invented narratives. Yvette Molina takes the female mythological figure further, remaking her as volcano, as a fountain of the earth’s primal energy. In crafting a revolutionary figure, Didier William avoids the determination of gender entirely, presenting images of the Black subject as an all-seeing fighter who negates the entrapping gaze of the colonizer. And Jesse Krimes shows us the power these ambitious visions of our possible futures have when made by those who have been incarcerated.

To paraphrase the poet Cyrus Cassells, I trust these artists to make a path for us — through shouting.